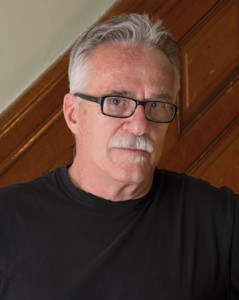

Photojournalist Greig Cranna has been serving diverse clientele since 1976. During his early years in New York City, Greig worked with the Council on Foreign Relations, the Japan Society, ABC Television, and the U.S. Department of Energy. In 1978, a QLF assignment sent him to the Quebec North Shore, where he began a thirty-seven-year love affair with the Canadian East and a long association with QLF. Greig has traveled extensively in the Canadian Maritimes, photographing seabird research, Atlantic salmon research, aquaculture, environmental issues, and ecotourism. In 1982 when he moved to Boston, Greig’s interests expanded to include education, agriculture and architecture. Though never a staff member, Greig has participated in and photographed countless QLF programs, from Canada to Long Island Sound, Hungary to Argentina. He has played an invaluable role in promoting the QLF mission for more than three decades.

Photojournalist Greig Cranna has been serving diverse clientele since 1976. During his early years in New York City, Greig worked with the Council on Foreign Relations, the Japan Society, ABC Television, and the U.S. Department of Energy. In 1978, a QLF assignment sent him to the Quebec North Shore, where he began a thirty-seven-year love affair with the Canadian East and a long association with QLF. Greig has traveled extensively in the Canadian Maritimes, photographing seabird research, Atlantic salmon research, aquaculture, environmental issues, and ecotourism. In 1982 when he moved to Boston, Greig’s interests expanded to include education, agriculture and architecture. Though never a staff member, Greig has participated in and photographed countless QLF programs, from Canada to Long Island Sound, Hungary to Argentina. He has played an invaluable role in promoting the QLF mission for more than three decades.

Article and photos by Greig Cranna

QLF Experiences

Photojournalist, 1978–present

For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved the road. Through the rapidly accumulating decades I’ve hitchhiked and driven tens, if not hundreds of thousands of miles; often for photographs, birds, and adventures, often for work, but mostly just in an endless, restless quest to find stuff out. There’s nothing like entering a region by road, each mile dripping nuance and dropping clues, helping to situate a place in your mind and feel the zeitgeist of the area. From the colorful farms flashing by as you make the long agricultural traverse into Montreal, to the relentless, winding climb up The Grapevine that leaves you gaping (and gasping) at Los Angeles laid out beneath you, the world is filled with roads that lead you, newly informed, to your destination.

My first foray into QLF territory in 1978 was by plane, and I have to admit, despite my Canadian upbringing I really didn’t have a clue where I was going until I actually located Chevery, Quebec, on a map when I got home. Obviously, that changed as the years went by, and for most of my myriad QLF assignments in subsequent years, I was far more likely to drive than fly. With all those miles came a deep and anecdotal understanding of the geography, the people, and the issues and changes that concerned and confronted them. The point is, there’s no substitute for driving to get a handle on a place, so when I set out this summer to write about QLF’s past and future, I never gave it a second thought…this would be a driving adventure.

Gathering for a last picture at the Josh Nove Viewing Platform, Perroquet Island, Quebec

As is typical, I left Boston with an agenda and a kernel of an idea for an article, then watched as it mutated as I piled on the miles. I left looking for a reason to continue my involvement with QLF and decide whether I thought there continued to be a place for QLF in this arena, or any arena for that matter. Where were the successes, where were the failures, where was the future? Was I the right person to make that judgment? Certainly I had enough knowledge and perspective to at least add my voice to the chorus. For 37 years my role at QLF had been as an outsider with an insider’s access and knowledge. I’d covered countless programs as a photographer, participated in conferences, congresses, and retreats, and written for many QLF publications. On occasion, I functioned as the skunk at the garden party; often bringing unwanted criticism and assessment to what at times could be a self-congratulatory love fest.

The road to St. Paul’s River, Quebec North Shore

But I’d stuck by this organization for all this time for a multitude of reasons; a love of the region and its people, the organization’s underlying mission, and the cadre of true believers who have shepherded it through many tumultuous decades. Thirty seven years ago I met Larry Morris in a coffee shop by the U.N. in Manhattan, and he stuck his neck out and took a chance on me; a young, green photographer with an idea for a film. Over the years I saw him do this over and over; not just with individuals and organizations, but more importantly, with ideas. Some of the ideas, and more than a few of the individuals went nowhere, but I always admired his unflagging daring to take chances. It was, admittedly, frustrating to watch at times, but was ultimately an approach that led to QLF’s survival, and its growth as well. A lot is being written lately about the importance of not being afraid of failure, and its role in personal development and the development of big ideas. I have to say, Larry Morris was on that train a long time ago, and has been unwittingly inculcating this message in young people for decades.

It’s no accident that QLF has beaten the odds and survived into this millennium. Around since the 1960’s, it has survived the counterculture years, the disco years, the dot com bubble, the financial crash of 2008, and the ever- changing funding landscape, to name just a few. Despite the perception of many that the organization has strayed drastically from its original mission, the reason it’s still here is that it is very much on the same mission that Bob Bryan laid out in 1962, and that mission is as relevant now as it was then. There are dead offshoots on the QLF evolutionary tree, and the theater of operations may have expanded geographically, but these are merely chimeras that have led casual observers away from the central truth: the Volunteers of the 60’s have become the Interns of the present; plain and simple. The core tenet of QLF has always been, and still is, that when you put young, idealistic people in contact with people culturally different from them you are creating a symbiotic relationship. They can, and do, bring much needed program assistance, but what they bring to the community pales in comparison to what they take away; you’d be hard pressed to find a QLF Alum who has not been altered by their experience. One of the most important initiatives currently underway at QLF is the amassing of this Alumni information into what is being called the Global Leadership Network. For the first time, QLF will have an accessible, interactive, workable handle on the 5,000 plus players who have passed through the organization, and will be in a position to facilitate the building of teams to attack problems anywhere in the world.

Looking for birds, Main Brook, Newfoundland

So, basically what I decided to do with this assignment was get out there, meet this year’s crop of Interns, and pick their brains, while pretending I was there solely as a photographer. Along the way I hoped to gain insight into the relevancy of QLF, and the Intern experience as well, in a rapidly changing physical, educational and technology environment. If I were lucky, I’d suck enough good information out of these interviews to wrap my article around and reach some conclusions that might be of use to someone. The end of the road for me would be Red Bay, Labrador, just north of the Straits of Belle Isle that separate the island of Newfoundland from mainland Labrador. It’s about 1,500 miles north of my home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and used to be the end of the road. It now continues up the coast a bit, then connects to the interior “city” of Goose Bay by a 350 mile, recently paved road. Nonetheless, it still feels like the end of the road, and would be for me, because my subjects, spread around the province throughout the summer, would all eventually end up there at the same time I would. With that as a goal, my plan was to drift northward, spend time with the Interns, drift southward and leave myself open to inspiration and epiphany along the way. Funny thing is, that’s pretty much what happened…

The end of the day, Point Amour Lighthouse, Labrador

This was a trip into the very heart of the QLF creation story, where Bob Bryan had begun working in the 1950’s and where QLF was created in the early 1960’s. I, too, have spent much of my life travelling and working in the area and was eager to gauge for myself how the future was being received there. There’s no question that the region Bob Bryan encountered in the late 1950’s is still a unique and special environment, but the changes in the intervening years have been rapid and profound.

Interns counting Common Eider nests, Saddle Island, Labrador

To a newcomer the changes aren’t glaringly apparent. Unlike so many fast growing areas of the U.S. and Canada, there isn’t a sense of sprawl, development and loss of physical open space. There are still moose caution signs everywhere, and still hundreds and hundreds of miles of deep forest-bordered roads. Driving north you encounter subtle physical changes; a wider faster road through the Maine woods to the New Brunswick border, wind machines at the head of The Bay of Fundy, and faster, more efficient ferries. Although the overwhelming feeling is that you’re still travelling through a vast wild area, there are subtle signs of change everywhere that are less likely to jump out at a newcomer. Many of them are positive; recycling bins in public places, water use reminders in the motels, and the absence of the pulp mill stink that hung over Saint John, New Brunswick, for decades. The introduction and embrace of snowmobiles in the early sixties brought the end of travel by dog sled, and the loss of a picturesque, romantic image of the north, but enabled an unprecedented level of social intercourse between remote villages in the winter. The introduction of satellite dishes, followed quickly by the internet has expanded that social intercourse even further and brought the contemporary outside world, for better or worse, into every village.

First binoculars, Main Brook Newfoundland

Many of the negative changes are far more subtle. The crash of the cod fishery in the 80’s has wrought a social apocalypse that is basically invisible to the eco-tourist or casual traveler; the paucity, or complete absence of working boats on the water, the shrinking and graying population of most, if not all of the coastal towns, and the subsequent miniscule number of incoming kindergarteners to the local schools. Even harder to see, but more pernicious, is the community cohesiveness that went with the fish. In the Labrador Straits many people spend much of the year in the mines in Northern Labrador, the hydro projects of Northern Quebec, or the tar sands of Alberta. As a result, there’s plenty of money, with well-maintained houses, new trucks and snow machines evident everywhere, but the erosion of community and culture is the by-catch. More than once I had older people tell me, “When we lost our fish, we lost our families.”

The end of the road, Red Bay, Labrador

Once in Newfoundland, I worked my way north from the Codroy Valley to Red Bay on the Labrador Coast, gradually peeling the Interns off individually for a little one on one. During long car rides, ferry trips, and casually over coffee we talked about a lot of things: QLF, life, music, parental expectations, you name it. I sold it to them as research for a potential article and the GLN database, but what I was really after was impressions. I wanted to see QLF, the region and the Intern program through their eyes. I wanted them to trust that they could speak openly to me, so I promised no attribution, no names…after all, I was looking to paint a landscape, so there was no need to identify the people in it.

Roadside waterfall, Bradore Bay, Quebec North Shore

Not surprisingly, there was quite a range of thoughts, motivations, and opinions. Some had come with rigid expectations and were finding it hard to have them met. Others had come with few expectations and were reveling in the mutability and flexibility required to work in an area like this. Surprisingly, many of them loved being basically off the grid. For a generation that appears to be always connected, not having reliable or regular Internet access made researching for presentations more difficult, but forced a new level of creativity on them that many saw as an unexpected bonus. Other unexpected bonuses came with the wildness of the territory; where else can you take a break from your computer and get chased down your driveway by a territorial moose? It happened more than once. Scary, but great dormitory stories when you get back to school in the fall. More than one interviewee mentioned the “cool” factor in picking this Internship. More than one acknowledged that there were Internships out there more suited to their major, but they were attracted by the chance to have a unique experience in a place they knew nothing about. Unsaid, but I think implied, was that just getting away from what you know and are comfortable with possesses value. From my first interactions with Interns in 1979, I watched the QLF experience forge lifelong friendships and bonds, an added benefit as many of them moved forward in similar career paths. Half facetiously, I asked two of this year’s crop if this experience had made them friends for life. Without an ounce of hesitation, and without even glancing at each other they both immediately answered, “Yes.”

As rapid as the changes to the region seem to some of us, it must be remembered, that to these young people it is still a remote and exotic area. The difficulty of access, travel, and weather bring the side-benefit of wildlife, icebergs, and people with different accents, aspirations, and motivations. In short, it’s the kind of place that broadens perspective and fosters unit cohesiveness. Interns quickly learn how to problem solve; within themselves, between themselves, and certainly with the environment. It’s not always an easy environment to operate in, which makes it a perfect place in which to toss a bunch of young people. Some years it can feel like QLF’s version of “Survivor,” but rarely does anyone get voted off the island.

In the summer of 1974 I was a 23- year-old Intern on a scientific team on the upper Yukon River in Alaska. Times (read, technology, and liability) were very different then. We were far off the grid; no cell phones, no radios, no satellite phones. I learned a lot of unexpected things in those months; I learned self-reliance, how to operate safely far away from help, and how to navigate the big, fast, muddy Yukon in a 20-foot boat. I also learned, three weeks after the rest of the world, that Nixon had resigned his presidency. But, the most important thing I learned was what I didn’t want to be. I had always loved science, and with a scientist father, I had always assumed that was where I would gravitate. Luckily, my Alaska experience nudged me in another direction, and I am forever grateful for finding that out early in life. One of the overriding impressions I came away with from this summer was how young college students really are, and how important experience is to the gradual deciphering of the complex set of emotions and motivations that come with that age. Although many of our gang had strong ideas about their direction, many were less certain, and a few had no idea yet. Even so, most possessed a remarkable sense, on the surface at least, of self-assuredness; full of the creativity and invincibility of youth.

I think it would be a self-aggrandizing mistake for QLF to think it’s altering everyone’s life through their Internships, but I think it’s a reasonable goal to attempt to foster and harness this sense of possibility and creativity as young people work to figure out their direction. Or directions for that matter. More than one of this group spoke of how their generation has no interest in being in the same career for their whole working lives. Through experiences like this they can try on different ideas, either checking them off the list or adding them to the pile of maybes. It may or may not be the defining experience of their lives, but it’s sure to be more than just a couple of threads in the fabric of who they ultimately become. I can’t think of a better place to explore and study biology, environmental science, geography, history or cultural anthropology to name just the obvious. With deep, historic roots in the region, QLF is in a unique position to use the entire area as a gigantic field station, while still providing valuable program assistance to the local communities. The empowerment that has come with the Internet and its access to resources has certainly altered the dynamic between QLF and the communities, but it has also expanded the scope of collaboration possible between them. That ability to forge collaborative relationships is what will keep QLF relevant and active in the region, and elsewhere, for years to come.

Another successful Youth Leadership Workshop, St. Anthony, Newfoundland

In St. Anthony, at the very northern tip of Newfoundland, the Interns spent much of the day at the Grenfell Museum leading workshops for local middle and high school students. Sir Wilfred Grenfell had built hospitals and clinics throughout Newfoundland and Labrador in the late 19th century and early 20th century and was an early inspiration to Bob Bryan, so it was only fitting that we should be back there with Interns. I cruised the periphery taking photographs, and when they were done, bundled up with them and headed down to the dock and boarded a waiting boat. After hours of interactive workshops on seabirds, whales and ocean health, we were now off to see the real item. We steamed out of St. Anthony harbor and quickly started picking up Black-legged Kittiwakes, Common Murres, Black Guillemots, and Northern Gannets. In the distance whale blows erupted around a massive iceberg, so we headed in that direction.

You know, sometimes it’s hard to avoid metaphors, just as it is clichés and platitudes, because they’re just so spot on. As we circled this beautiful chunk of ancient, floating ice, the captain did a nice job of explaining its origin (Greenland), its age (circa 12,000 years), and the always-impressive fact about the bulk being below the surface (90%). With thoughts of the developing Global Leadership Network continually circling in my head, I saw the specter of metaphor appearing, literally in front of me. As QLF has progressively shrunk at the staff level, its bulk has grown continually below the surface. It may appear lean and mean on the surface, but its bulk and strength derive from that giant reservoir of human talent just below the surface. Ernest Hemingway invoked the concept when he wrote, “The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”

Last lingering iceberg, Strait of Belle Isle, Labrador

As I spent more and more time around these Interns, I was continually and nostalgically reminded of myself as a young person in the field for the first time. Anecdotes and experiences are evidence of a life well-lived, and I have more than my share, but as the years pile on it’s all too easy to have some of the jagged excitement of newness get filed down. As the firsts started to accumulate for this gang; first iceberg, first whales, first caribou, and first taste of capelin, their excitement started to rub off on me, and I started seeing things through their eyes. Nowhere was this more evident than when we made our crossing to Labrador the next day. I had been answering questions about my life and career, and dispensing advice (some of it unwanted I’m sure), for a week, and was gradually reaching the idea that we of the old guard had plenty left to offer. Youth and vitality are generally no substitute for knowledge and experience, but the symbiosis of the two was becoming more and more apparent to me. The high point of this trip came during this crossing. We arrived at the ferry landing in St. Barbe in a number of vehicles, put our cars in line, bundled up and hung around eating snacks, taking group photographs and waiting for the boat. Their excitement was contagious. None of them had ever been to Labrador, but they couldn’t wait to get on that ferry and see for themselves the place they had been told so much about. We spent the entire time on deck counting seabirds and spotting whale spouts… enthusiastic, but all business until we started to close in on the coast. The first Atlantic Puffin fly-by got the whoops started, but it just got crazier from there. Soon they were everywhere; flying in all directions, joined by Common Murres and Razorbills in massive rafts on the water and swarms in the air. Then, out of nowhere a Pomarine Jaeger with full breeding plumage “spoons” trailing behind rocketed right down the side of the ferry. The frenzy on the water was matched by the frenzied excitement on deck, until the whales started putting on a show and kicked it up a gear. Between us and Ile au Bois were thousands of seabirds, in the air and on the water, their rafts being blown apart by breaching and lob-tailing Humpback whales. Now my crew was literally jumping around, shrieking, and hugging each other in disbelief. It was a hilarious and infectious moment of excitement that had them (and me) buzzing long after the ferry docked and we disembarked. Never had it been so clear that experience for vitality was a trade agreement I wanted to embrace, and was an obvious one for the long-term health and evolution of QLF as well.

One foggy morning in L’Anse au Clair I braved the black flies and wandered down to the cemetery that sits 30 or 40 yards back from the beach. Almost 25 years ago I battled black flies while attempting to shoot the crosses of the graveyard against the backdrop of a flotilla of icebergs. The flies made it hard to change lenses and more than once I could see them crawling on the mirror. In those pre-digital days I had no way of removing the dots and streaks made by black flies, but I did come away with a few good pictures. One was of a very old wooden grave marker lying on its back, disappearing into a nest of sphagnum moss. This morning, as I searched futilely for it, it was hard not to see it as a metaphor for the vanishing culture of the coast. Would this shrinking population of the Labrador coast ultimately go the way of the Basque whalers who first settled it in the 1500’s? Love of place, history, family, and tradition are powerful forces, however, and I’m sure there will continue to be human presence here for a long time. As in so many remote places, ecotourism, although very seasonal, is growing as an economic force. The same attributes that make this such an ideal place for QLF to work also lure the buses across the Straits. The appeal of the end of the road, the walk down to L’Anse Amour light with whales cruising just off shore, and the mystique of foggy, iceberg clogged harbors will hopefully keep ‘em coming.

Bringing in the Capelin nets, L’Anse-au-Loup, Labrador

On my last night in the Straits the surfeit of buses had consumed the all too few motel rooms, and I was forced to find a room in one of the few B&B’s around, 30 minutes up the coast from

the ferry in L’Anse au Loup. Down at the beach, a handful of small boats was enshrouded by screaming gulls as nets full of capelin were being hauled in. It felt like the old days, and the sight of men working nets seemed to infuse the whole town with electricity. Later, when I checked into my B&B I was ushered into an immaculate, small house by a very staid older woman. She, too, was immaculate, but dour. All business, no smiles. That all changed, however, when I mentioned that I’d been photographing the boats hauling in capelin. She lit up, instantly, like a schoolgirl in front of a birthday cake as she urged me to get down there where they’d be giving away samples. For a few moments she was transported; the triggered memories visible on her face. It was touching, but heartbreaking; like watching an extinction take place before your very eyes.

However, despite the changes, it’s still a place of unimaginable beauty, hardship, and surprise. With a great cup of coffee in my hand (positive change), I left L’Anse Au Clair with a Short-eared Owl flying alongside me, drove through Blanc Sablon, and parked across a narrow strait from Perroquet Island. I nursed my coffee and toggled my binoculars between breaching whales, and thousands of Razorbills, Atlantic Puffins, and Common Murres. It was my last day with the Interns and I was waiting for them to show up for goodbyes and photographs. Apart from the wildlife spectacle, I had chosen this spot for a reason. At the end of a dirt track, in a meadow of moss and reindeer lichen sits an observation platform equipped with telescopes. It was built to honor Josh Nove, a QLF Intern who charmed, and was charmed by, the people of the Coast many years ago. He was a brilliant, up and coming ornithologist and was destined to be one of QLF’s superstar Alumni. He drowned after stepping off an invisible shelf in silty water while conducting bird research in Alaska in 1997 on assignment with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. His body was never found, but his spirit lives on here and in all the eager Interns who have followed in his wake, many of them on this very coast.

Late summer evening, Codroy Valley, Newfoundland

My trip back across the Straits alone was palpably different than the one a week earlier. Without my young compadres I was alone on deck the entire trip. Most of the locals, having made the trip many times, were inside sleeping or playing cards. This time there were no whoops when a Northern Fulmar or Pomarine Jaeger flashed by, no gasping when a pod of Killer Whales surfaced behind the ship. I had come looking for inspiration and direction, and the lack of vitality and energy on this passage was the answer writ large. The thing that had made this trip so special, and QLF by extension, was the chance to be exposed to the enthusiasm, life, and incredible potential energy possessed by this next generation of leaders. Just the latest collection in a long continuum stretching over 60 years, they are the heart and soul of this organization and are the obvious answer to any questions about the relevancy of QLF. Arguably, the world is a more complicated place than when I started with QLF in 1978. Environmental issues, if not larger, are at least more likely to be better understood as global issues affecting us all. This alone, is justification for QLF taking a more global approach in its operations. I see a model where Interns are steeped in QLF lore while working in the “home” region, then move to another level of Internship either here or elsewhere in the world. This approach would enable QLF to maintain its core in the region it knows best, but still be engaged on a global level. Despite the forays into other parts of the world and an ever-growing international awareness, this is still the world that QLF knows best. It is not the same as Bob Bryan found it in the late 50’s, but it is still an area critically important to QLF identity. This is where for decades bright, local youth were found and nurtured into becoming nurses, pilots, teachers, and even QLF Board Members. This is also where hundreds of Volunteers and Interns saw their first icebergs, puffins and whales, and charted the course of their life’s journey.

One night after dinner in West St. Modeste, I took one of the guys out to try shooting some long-time exposures of a large iceberg that was grounded just offshore. My idea was to put a deep neutral density filter on the lens and shoot ten-minute exposures in the quickly failing light. The concept was to have the long exposure turn the moving ocean into a soft, dreamy blur, while the rocks and iceberg remained sharp. We timed the exposures on an IPhone and periodically checked our progress on the back of the camera as it got progressively darker. We were amazed to find that while the rocks were sharp, there was still a little movement in this giant, grounded mass of ice. Ah, back to the metaphor. Even big, seemingly, immobile objects can continue to move. Just as amazing, we were surprised to see that in each 10- minute exposure, the large fissure on the left side was growing. Finally, it got too dark to shoot and we returned to the motel where the rest of the crew were waiting. When we got up the next day to head up the coast, there had been more change. Dozens of bergy bits had broken off in the night and were drifting off on their own voyages. QLF diaspora? Take a look at the Global Leadership Network when it’s launched and reach your own conclusions…