Leslie Van Gelder, Ph.D, is an archaeologist, writer, and organizational change strategist who lives in the Rees Valley of New Zealand. She credits her early years at QLF with having shaped her interest in place and story and her love of rural communities at the edge of wild places. She is author of Weaving a Way Home: A Journey of Place and Story, which features stories from her summers on the coast. Her archaeological work on the role of children as cave artists has been featured in World Archaeology, Archaeology Magazine, and Antiquity.

Leslie Van Gelder, Ph.D, is an archaeologist, writer, and organizational change strategist who lives in the Rees Valley of New Zealand. She credits her early years at QLF with having shaped her interest in place and story and her love of rural communities at the edge of wild places. She is author of Weaving a Way Home: A Journey of Place and Story, which features stories from her summers on the coast. Her archaeological work on the role of children as cave artists has been featured in World Archaeology, Archaeology Magazine, and Antiquity.

QLF Experiences

Ocean Horizons, Newfoundland, 1985, 1986

Marine Bird Conservation, Harrington Harbour, Quebec, 1987

Robertson Lake Canoe Camp, Robertson Lake, Quebec, 1988

Labrador Oral History Project, Forteau, Labrador & La Tabatiere, Quebec, 1989 QLF Alumni Congress, Hungary, 2006

My QLF history begins not with my own experience, but with a story. In the summer of 1977, my father came home from Botswana with a story of a man who’d been carried off by a lion for having slept too far away from the fire, and a pair of Cornell graduate students whom he’d ‘adopted’ for the week at his tent camp after their travel companion had been helicoptered out. (He lived, by the way, in case you’re wondering). It was a unique story in that we’d never heard a story of anyone actually being foolish enough to sleep far from the fire in Africa and equally that my father came home singing the praises of one of those graduate students who was going on to do ‘real work,’ work my father thought mattered. He wasn’t a man of much praise and the young Cornell graduate who had impressed him so was a young Larry Morris who had just returned from Botswana and would soon work for Bob Bryan. The rest, as some would say, is history, but I like that my QLF story begins close to the genesis of Larry’s own, as I have had the rare privilege of being able to participate in some of QLF’s history with my own experiences, and watch and learn from the sidelines as well.

Without irony, my first experience with QLF also took place in east Africa. During the summers of 1983 and 1984, my father offered safaris to Kenya and Tanzania to the QLF community as both an experiential and fundraising opportunity. I accompanied my father on trips during both of those summers, the first with a different group, and the second on a trip where I roomed with QLF Alumna Liza Carter and travelled with her family, Tom Horn, and his mother, and some others who were interested in east African wildlife. Though we spent our days looking through binoculars at lions and marabou storks, Tom and Liza filled my head with images of coastal communities and summers spent teaching environmental education and living in places I could imagine but hadn’t yet seen. Needless to say, when Tom asked me if I’d like to be an assistant instructor at the next summer’s Ocean Horizon’s Program, I don’t think I even let him finish the question before saying, “Yes.” I was fifteen years old and the romance of working some place as remote as Newfoundland deeply appealed to me. I came home from Kenya, bought myself a blue three ringed binder, the type my father used for his field notes, and began researching anything and everything I could find about Newfoundland.

I probably should have started with “how to pronounce Newfoundland” as I keenly remember getting that wrong during my orientation the following summer in Ipswich. Still, my notebook was filled with information about birds I might encounter, geological history, marine life, and something of the political history, though I would learn that first hand from old timers who would later tell me all about Confederation and why it had been such a bad idea. I had been raised on AAA guidebooks and I think in my own teenage way, I was probably trying to create the same. Something that would orient me to a place I had never been before. But truthfully, nothing but ‘being there’ would be a real education when it came to Newfoundland in the summer of 1985.

After a brief orientation in Ipswich that summer, the rest of the group drove up to Rocky Harbour while I flew home to take my final exams and then flew up to Deer Lake on my own. It had been a long day having flown from LaGuardia to Dorval, navigating an immigration officer who wanted to know why a high school student from New Jersey was going to be working for free in Newfoundland of all places, and then boarding an Eastern Provincial Airlines flight for Deer Lake.

For the entire flight, I looked down at landscape below in greys and greens, fog and clouds drifting in and out of mountains worn smooth by ice age upon ice age in the past.

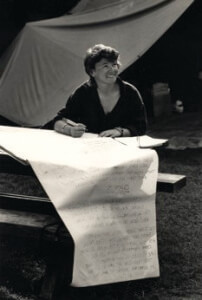

Leslie Van Gelder, QLF Intern, Ocean Horizons Program, Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland (1986). Leslie worked as a QLF Volunteer and Intern on conservation and environmental education projects in Newfoundland and on the Quebec North Shore during the 1980s.

When the plane landed in Deer Lake, I expected my new companions from orientation to be there to meet me, but as the waiting room emptied I was completely on my own. For hour upon hour I sat as the day turned to dusk and I worried that no one knew I was coming and how exactly would I get back home again if no one ever came for me? The 1,500 miles between home and Deer Lake suddenly seemed an enormous gulf.

As the day faded, a yellow van pulled up at the side of the road and out piled Danny Yoon and Ralph Jarvis full of apology. The road was being built through Gros Morne National Park that summer and as I would learn during my summers on the coast as paved roads arrived in a number of places, a dirt road was becoming a paved road, and that process is never an easy or painless one. What they thought would be a short trip had been far longer than expected. I was so relieved to see them that I’m not sure I even listened to what they had to say, but was very happy to drive north back up to Rocky Harbour and to Green Point where my summer in Newfoundland began.

Our camp was a beautiful thing. Set up on bluffs shielded from the coastal winds by a band of trees and windswept tuckamore, two old canvas tents had been pitched for the staff, ours christened the Puffin Palace, the men’s tent no doubt also well named but that memory long forgotten now. Bright green Eureka tents for the campers set up in a semi-circle around the trees to protect them from the wind. Beneath tarps that presented physics problems with every rainstorm as to having to work out just where to stand so as not to be the one on whom the whole weight of the day’s rain could fall in an instant, we built a kitchen of a green coleman stove, pots and pans, and crates of food that only barely and occasionally resisted the vole population that was in plague that year. Across the camp we had a supply tent where I spent many a rainy Sunday afternoon labeling old army cups with names like Aaron, Dwayne, and Cherise, in preparation for our campers who came to us from the neighboring communities. Like them, I had never slept in a tent before, much less spent nights down at the beach learning the names of the stars. But unlike them, I didn’t want them to know that I didn’t know so much, so I listened and listened to my sage fellow instructors who seemed to know the names of the birds and the stars, and all of the carnivorous plants in Western Brook Pond, and a thousand other things that their years in college and out in the bush had taught them.

Gros Morne National Park, Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland. The national park was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

Mostly that summer, I fell in love; in love with the Coast and the way the waves pounded the rocks at Green Point. In love with the trilobites, we took the kids to find fossils in the rocks or the tiny sundews in the bog that were feasting (but not quickly enough) on our constant black fly companions. I learned how to make spaghetti a la Simon and Garfunkel when one of the instructors taught me it all had to do with Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme. I learned how to teach by creating moments of discovery, how to use theater as a way of teaching ecology, how to walk barefoot across a tidepool, and how to move so quietly that a herd of caribou wouldn’t hear you approach. I learned the names of whales and the history of some of the oldest mountains on the earth, and learned from the parents of the children who came to our camp, a generosity and a language spoken in fresh baking – moose stew, and fish for our days off.

Gros Morne National Park, Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland

It was all new and I don’t know if I have ever felt as alive as I did that summer. Kass Hogan, who led our camp and taught me about quiet leadership through example, let me teach my first lesson — one on how to write about nature — to our first session of campers. I can see myself now, trying to articulate the same thing I am doing today as I write this — finding words for the inexplicable wonder of the world. I asked the kids to draw pictures instead of finding words, and in time we wrote poems and then chronicles of our days. My own journal from that summer reads like a photo album of moments caught in words about colors of sunsets I had never seen before and stars seeming to come straight out of the ocean and fly into the air with the same force of the sea spray. There is little about the day-to-day nature of our camp, except the small moments where one of the campers fell asleep with his head in my lap during a campfire or one of the young girls told me that when she grew up she wanted to be a teacher, too. I didn’t know I wanted to teach then, but the summers I spent working for QLF made clear to me that I did. They also made clear to me that I didn’t want to have a future making grilled cheese sandwiches.

And so the pattern of my summers began. From 1985 to 1989, for five summers, I worked in QLF programs in Newfoundland and Labrador and Québec. While I often don’t always clearly know where my life is going, when I look back, I can trace many of the routes I’ve taken in my life to things, which have their genesis in my experiences on the Coast. These include having become an educator, and a writer. In my early 30’s doing an interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Experiential Education and Place Studies had its roots in experiences connecting children from Rocky Harbour and Harrington Harbour back to the world that was right on their doorstep but one for which they didn’t know how or where they connected. No amount of experience in classroom teaching ever came close to the transformative power I found in introducing young people to the wild.

Today, I live in a community in New Zealand of 250 people that borders one of the largest world heritage protected wilderness areas, and every day I am confronted with the same questions we asked in Harrington and Cow Head and Forteau. Questions about heritage and sustainability, questions about the younger generation and the older, questions about the tensions between fishing and farming and national parks and finding ways where the future exists for all. When I told Larry Morris that I was moving to a community of 250 people at the end of a road in New Zealand, he laughed and said, “At least this time you have a road,” in reference to a summer spent in Harrington Harbour where we lived on an island with a community of a similar size. He knows why I am here and how strong the ties are between what I learned and experienced on the coast and how much it applies to the life I lead here. Just like in Harrington, I still live in a place where no one locks their doors.

So my first five years with QLF were what I think of as an apprenticeship. An apprenticeship in rural living, environmental education, and folklore, as I was involved in all of those pursuits equally. But those are only half of the apprenticeship as the other was one that is harder to articulate but perhaps more important as it was something rare, and as I got older, I discovered just how rare and unique QLF was — an apprenticeship in leadership and integrity.

Like many, my summers with QLF taught me about leadership in two ways. First, I was offered opportunities galore. Opportunities to teach something I had just learned myself. Opportunities to experiment, try out new ideas, learn from experience and combine the best of the arts and sciences to develop meaningful experiences for the kids who came to our programs. As an educator we were given freedom to be creative and freedom to develop programming that allowed our own personal passions to reverberate with the young people we met. There is nothing more contagious than being in the presence of someone who loves what they do, and the kids in our programs were in the presence of artists and musicians, athletes, and passionate birders. They couldn’t help but be inspired. I certainly was.

In those ways, my Internships probably paralleled those of other friends who worked in similar type programs. The difference, to me, was that I also was being mentored in what good leadership looked like from the other side, too. We were led with the same respectfulness as we hoped to lead ourselves.

Every summer we began with an orientation program that gave the Interns a chance to bond, but also a chance to be exposed to ideas and approaches that we would be using in the field. Years later, when I worked more professionally in experiential education, I realized that I had learned from the best. Plain and simple. What I learned in 1985 as our Ocean Horizons day-to-day normal was light years ahead of other places. More, though, every summer Larry Morris and Tom Horn asked us to evaluate the summer and from the perspective of a 16 year-old Intern, the idea that the director of the programs really wanted our feedback and took the time not only to read our reflections but also to sit and talk with each of us about what had gone well and what could be improved was extraordinarily empowering. This wasn’t lip service. They listened, made changes where they could and explained when they couldn’t. In the off season, they kept in touch, cared, and were glad to hear of future adventures. They modeled true leadership in the model of humble leadership, and to this day, 30 years later, I have never worked for anyone else who has exhibited those qualities so honestly and completely.

They ruined me for anyone else.

I thought in the schools where I worked when they asked for feedback that they would care as much as Larry and Tom (and later Beth Alling) did. QLF’s leadership exemplified integrity and in the 30 years I have been connected with QLF, this has been and continues to be at the organization’s core. It is rare in the world these days and perhaps because I have known it since I was 16, I believed I would find it everywhere instead of perhaps in as remote places as the communities QLF has always served. That model of leadership — of listening to every member of the team equally, of mentoring, of helping people make connections, and of caring what happens to the people with whom you’ve worked — has stayed with me my whole life. It is the model on which I have drawn again and again in helping other organizations learn how to be truly good. Few want to put in the time. In an organization where the President has been in the same role for over 40 years but every year has made that role interesting and unique, the concept of time functions differently. It functions the way communities do instead of the way corporations do. And in that, its foundations and its strength are always and ever in relationships. Relationships that are built, maintained, and strengthened over time.

The legacy of the model of leadership QLF offered its Interns is unique in that it was and is real in fostering one’s own capacity to be a leader and equally in having mentors who exemplified what it means to lead with humility. These days it might be easier to find an unexpected great auk than such a thing, so in this, I feel as though I have been a beneficiary of an extraordinary education.

I was 20 when my first era with QLF ended. Like many, I kept in touch with Larry, through his hand written annual Appeal, which always prompted me to send a letter back keeping him updated on my adventures. I noticed that at times in life when I was on the cusp of a career transition, I often found my way up to Ipswich, and happened to be able to catch up over a lunch in an office that often felt comfortingly unchanged over time. Larry’s guidance was always sound, and over the years I followed the path of QLF with appreciation for its International Programs and the way in which it was evolving. It had been so transformative for me, that I could only imagine the effect it was having in new geographies. The publications, full of photos of new places and that same warmth of smiles and groups gathered together kept me connected to the broader world into which QLF was now an even greater part.

Harrington Harbour, Quebec North Shore

In the winter of 2005, my late husband, Kevin, and I called in on Larry while en route to New Hampshire. Larry was excited about the prospect of a QLF Alumni Congress in Budapest (April 2006) I loved the idea of being able to reconnect with friends I hadn’t seen since my summers on the Coast. A few months later I was on a plane to Budapest where in the airport on arrival I was reminded of my first trip to Deer Lake as the mix of QLF people travelling together to the hotel in the van were as alive, inspiring, and as generous as the people I had worked with twenty years before on the Labrador coast. We came from all over, but there was a common bond of appreciation for QLF’s investment in us at an earlier stage of our lives and careers.

But this group was different, too. While my original experiences had been with North Americans, the Congress was far more culturally rich. Familiar faces from the past mingled with names and faces I had seen in Annual Reports and issues of Compass. Here were whole sessions devoted to the work of environmental educators from the Middle East and sessions about protected landscapes in Europe and Central and South America. I befriended a group of Jordanians, who told the best and worst jokes I’ve ever heard. Over beautiful meals, the conversations with the participants of the Congress were some of the most honest and affirming I had had in a long time.

I came away from the Congress thinking, ‘This is what it’s all about,’ and that QLF does it better than anyone. Gather good people, people who care about the future, the past, and the inhabitants of this planet, who fundamentally want to do what they can and see what

Harrington Harbour, Quebec North Shore

synergies come when you put them together. Donald (Obie) Clifford, Chairman Emeritus, Board of Directors, QLF-U.S., often says that there are only two questions in the world. The first question is about how we interact with Mother Nature, and the second is about how we interact with each other. He believes, and I believe it right there with him, that QLF is unique as an organization because it attempts to address both of those challenges and to provide leadership in finding answers. Many of those answers are about sitting down at a table together with environmental educators in a challenging political region who say things like “migrating birds don’t recognize political borders. They care that they have a place to land and food to eat. Surely we can work towards that?” Or the conversations I heard among tourism operators in places as diverse as the Labrador Straits, the British Virgin Islands, the Gulf of Oman, and Belize, talking about the exact same issues. There were places to see, there were trees to plant, good wine to drink, but most of all, there was an inherent energy of collaboration and creativity in working together to address issues that almost all of the Congress participants faced in their local communities but were challenges that recur and recur and recur around the world.

Perhaps because we had all been gathered together it was easier to see the seeds of a Global Leadership Network sitting in front of us. QLF’s Alumni were now leaders in their own communities and yet there was a desire for something more. Something that addressed and acknowledged the wealth of experience and capacity to think as creatively as we had all done in our first Internships, Fellowships, and Exchanges. Only now rather than be only regionalized responses, there seemed to be a great interest in applying what we had learned locally to aiding others in other regions and finding collaborative solutions.

Times had changed in the funding landscape of the world, too. In the days when I had first worked for QLF as an Intern there was a fair amount of funding for the kinds of programs QLF was offering. By the mid-2000’s governments were shifting their priorities, competition for what remained was growing fiercer, and some of QLF’s historical funders had passed away. It was time to think towards QLF’s future and begin to look at its options.

In the summer of 2007, Larry came to see me in Oxford, England, to talk about working together on a piece to look at QLF at 50 and to envision its future paths. All through that summer and into the fall, he, Beth, and I considered the options of what the internal structure of QLF could be and what trajectories it could take. We wrote a document that became known to us as The Four Options and it outlined four potential fiscal and administrative structures for QLF’s future. Eight years later, The Four Options still serve as our touch point to be able to help us define where QLF is going and what other options are available to us.

At the behest of then Board Chairman, Jim Levitt, in 2012, a Strategic Planning Committee was formed to look at whether or not QLF was on track with staying true to its programmatic Mission and looking to the future. The committee, Chaired by Jamey French, set themselves a daunting task of interviewing over 100 members of the QLF’s Governing Boards. Each interviewer asked the same questions and for the first time we were able to look at a set of quantitative data about QLF from multiple perspectives.

What we learned was enormously helpful. We learned that for the most part, people had a very clear vision of QLF. The central question, “Is QLF still relevant today?” turned out to be an emphatic yes and a strong dose of institutional confidence and enthusiasm for QLF’s future. The members of the Strategic Planning Committee, invigorated by the process, made Recommendations to the Board, which were accepted in 2014, and this current year has seen the implementation of new strategies that are the direct result of the input from the research exercise.

Simultaneously, the Global Leadership Network has developed from the seeds planted in Hungary and is taking shape and form in structure and infrastructure. As this is new terrain, there has been time spent well in exploring what will be the best ways to bring people together, to share knowledge and resources in a world of increasing capacity to do so, and to retain the creativity and generosity of spirit that has always been at the heart of what QLF has always done so well. Looking ahead to the coming year, I envision, the capacity for innovation and a recognition of the strengths of each individual within the broader QLF family will ultimately distinguish QLF from all of the others. There are roots, strong roots, that have taken 55 years to develop but they can allow for the kind of flourishing that few other organizations can hope to achieve. QLF’s community is like no other because it has always been first and foremost about relationships.

I have had the rare privilege to get to work closely with both Larry and Beth over the last eight years in a variety of roles, but largely as a listener. I hear their worries and concerns, and then invariably the conversation quickly switches to their contagious passion as they tell me a story about someone in the QLF family who is doing fabulous work, or about a new Intern Beth’s hired who is so bright and is doing amazing work, or news from Belize of more acres saved. I hear about the people they’ve met, the connections they’re making on behalf of QLF, and the bird that Larry saw this morning when he was taking the dogs for a walk. Mostly, what I hear, thirty years after I first arrived in Ipswich as a 16 year-old assistant instructor, is the same voice of inspiration, passion, and desire to do what one can with the time we have towards helping people and places navigate the challenges of right now and years to come while honoring their history and heritage.

So go ahead, sign me up for another 30 years. I get the feeling that in the lifespan of QLF, I, and QLF have only just begun.

Conclusion of Tree Planting Ceremony, QLF Alumni Congress Landscape Stewardship tour, Kiskunság National Park, Hungary, 2006